General Motors has been in business for more than a century, but in its 112 years, the company has never faced such challenges as it does in today’s rapidly electrifying and automating industry. The assembly line jobs from Detroit’s heyday have been replaced by legions of automated industrial arms, almost as quickly as the era of internal combustion engines has been supplanted by EVs. Since 2014, it’s been Mary Barra’s job as CEO of GM to help guide America’s largest automaker into the 21st century.

In Charging Ahead: GM, Mary Barra, and the Reinvention of an American Icon, author and Bloomberg automotive journalist, David Welch, recounts Barra’s Herculean efforts to reinvent a company that has been around since horses still pulled buggies, reimagine the brand’s most iconic models and bring EVs to the masses — all while being a woman in the highest echelons of a male-dominated industry. In the excerpt below, Welch examines some of GM’s earliest electric initiatives, like the popular but short-lived EV1 or the loss leader Bolt, without which we likely wouldn’t have many of Ultium-based vehicle offerings.

Battery-powered cars had captured the imagination of wealthy, tech-minded drivers. Tesla was the first to tap into that, becoming a hot brand in the process. Its cars began stealing customers away from the likes of Mercedes-Benz and BMW. But in 2017, when Barra was weighing up her own plug-in-play, EVs were still only about 1 per cent of car sales. They were still too expensive for most consumers and even at fat prices, they lost money. EVs sold by Tesla, GM, and Nissan could take hours to charge and only Tesla models could go more than 300 miles on a charge.

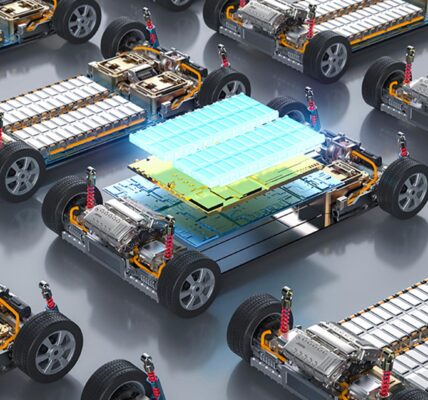

GM had been working on electric batteries and developing vehicles that would run on them. In no way was Barra flat-footed. But spending billions on cars with an uncertain group of buyers was seen as speculative and risky. Internally at major car companies, there were still voices saying that EVs were a costly science project. They assumed Tesla would run out of cash one day and carmakers could carry on as they always had.

Internally, GM was weighing uncertain demand for EV sales against the risk that Tesla and Germany’s Volkswagen group and even Ford would capture the buyers who made the switch. That threatened to completely reset customer loyalties and shake up the industry. Tesla already sold most of the electric vehicles on the market. Elon Musk threatened to upend the auto industry the way Apple’s iPhone did to ’90s mobile phone kingpins Nokia, Motorola, Ericsson, and Siemens. GM’s future hinged not only on Barra’s courage to make a move, but also on her being wise enough to get the timing right.

The caution was understandable. At the time, Tesla was by far the top seller of electric vehicles with 100,000 sold globally and losses of about $2 billion on sales of its Model S sedans and Model X SUVs. Those Teslas typically sold for more than $100,000 apiece, which is triple the price of the average gas-burning family SUV. With Tesla’s $100,000 cars losing money the challenge for companies to make a buck selling EVs was daunting.

GM knew it all too well. In the 1990s, the company sold the famous EV1, an aerodynamic two-seater priced at $34,000 that was leased to EV enthusiasts from 1996 to 1999. That was an expensive car back then. GM spent $1 billion developing it and would lose more money selling the vehicles, said [then-GM CEO G. Richard] Wagoner in an interview. I remember seeing a presentation for the car at the Detroit Auto Show in 1997. GM’s then vice chairman, Harry Pearce, talked about electric cars like the EV1 and also about hybrids that ran on gasoline engines and electric motors. For GM, it was a display of what the company’s engineers could do and a glimpse of the future, he told me. But it would be decades before it would be a real business.

The EV1 would bring GM serious credibility with environmentalists, but after leasing 1,100 of them, the company lost a lot of money. A few Hollywood actors like Ed Begley Jr. leased one and promoted it as often as he could. Francis Ford Coppola had one, and when GM ended the program and demanded that lessees return the cars, he refused to give it up and kept it. The company crushed all the cars that it had leased after retrieving them, which then made GM a pariah with the same environmentalists who loved the car.

The economics of electric cars weren’t very good twenty years later. Chevrolet started selling the Bolt in 2016 and lost a whopping $9,000 on every one of the $38,000 plug-in cars it sold. Before that, GM sold the Volt plug-in hybrid, which uses a gasoline engine and an electric motor in tandem to get forty-two miles per gallon. The Volt lost even more. Those nasty numbers would drive serious resistance to electric cars inside GM and at other major carmakers, too.

One big reason GM sold the Bolt was to meet government regulations. In California and a dozen coastal states that followed its lead, automakers had to sell electric vehicles or other super-efficient cars like hybrids to be able to sell their profitable gas guzzlers. Selling green vehicles earned ZEV credits. GM could also buy ZEV credits from Tesla, which many automakers did. But that just meant that they were helping fund Musk’s effort to eat their lunch.

In the EV race, Tesla already had the advantage of a tremendous amount of investor patience for Musk’s losses. Even though Tesla lost $2 billion that year, his company’s market capitalization ended in 2017 with a total value of $52 billion. That was just $4 billion less than GM’s even though Barra brought in near-record profits that year. In other words, the market would continue to fund Musk’s money-losing operation, but Barra had to fund her own vehicle development with profits from the very gas guzzlers she was seeking to replace.

That put GM and the mainstream car companies under pressure from three sides. Shareholders wanted profits from pickup trucks and sport utility vehicles. But in the car market, Tesla was stealing buyers, gaining a technological advantage in battery development, and building an Apple-like brand for making the cars of tomorrow. Meanwhile, governments were putting the squeeze on with new clean-air rules.