In The Face Of Global Trade Wars And Tempered Demand, Has The Battery Supply Chain In North America Lost Its Charge?

According to the International Energy Agency, the market share of EVs in the US (including plug-in hybrids) jumped from 0.2% of total car sales in 2011 to 4.6% in 2021, with similar adoption rates also seen in Canada and Mexico. However, this initial increase has stagnated in recent years. Speaking at ALSC Global last year, Criss Edwards, president and managing director North America at Unipart, explained that there was only a small increase in total market share from 2023 to 2024, from 7.5% to 8%.

Despite this recent slowdown, automakers have poured millions of dollars into the EV space, encouraging innovation at every stage of the value chain. Experts at this year’s Finished Vehicle Logistics North America conference were positive about EV forecasts and the steps that North American companies had taken to reinforce EV and battery production in the face of disruption.

At the conference, Thomas Shannon, finished vehicle operations manager for ports and logistics EV at GM, said that the most important parts of an EV and any associated logistics were “batteries, batteries [and] batteries.” The question is, how might changes to EV demand in North America impact this key component?

At a glance: highs and lows of the North American EV supply chain

President Trump’s culling of tax credits and rebates for EVs sent shockwaves through the EV landscape, leading many to worry about its continued growth. Even before the Inflation Reduction Act announcement, growth had stagnated compared to initial forecasts but remained consistent.

However, automakers of various scales remained optimistic, with both domestic and foreign OEMs pumping investment into improving EV production and logistics capabilities.

These nearshoring efforts alongside innovation in logistics infrastructure make the future of EVs mean that automakers are better equipped to deal with demand fluctuations, but uncertainty in forecasts remains high.

A major contributor in the rapid growth of EVs in the US market over the last few years has been the increased support for EV development and purchasing. The Biden administration’s Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), and the Chips and Science Act, both sought to encourage domestic EV production while making it easier for consumers to buy into EVs. The former legislation introduced tax credits for EVs manufactured in the US while the latter provided federal support for technical R&D into semiconductors, which are crucial for EVs. A 2024 report by Sucden Financial pointed directly to these regulations as being key to the growth of the EV market – as without them, there would have been no way to “accelerate the adoption” of EVs in the US.

Facilitated by federal support for research and increased consumer buy-in to the space, the demand for batteries skyrocketed and far outweighed the supply and production capabilities. This continued on a trend seen in the wake of the Covid pandemic where core battery materials – most commonly lithium, but also cobalt and nickel – were in short supply, leading to increased prices and resource competition. Despite these supply-side challenges, automakers saw success in the hybrid and EV space, with almost 20m units being sold in the US in 2022 alone.

However, very early into his new term, President Trump announced a halt on IRA benefits. This followed an earlier statement about revoking an unspecified EV mandate.

The response to this was mixed, with some suggesting it could help address the difference between demand and supply in the domestic US market for EVs. If such a slowdown occurred, it would relieve some pressure on the battery supply chain and potentially help level out the price of battery materials. However, others feared it would see EV adoption stagnate even further, resulting in wasted investment for OEMs and exacerbating existing fiscal pressures.

The Trump administration “paint[ed] a clear expectation for US policy direction in the immediate term,” according to Stephanie Brinley, associate director of AutoIntelligence at S&P Global Mobility, who was commenting at the time. Her prediction was correct, as a bill recently introduced by the House of Representatives seeks to remove several of the tax credits associated with EVs. That includes the Commercial Clean Vehicle Credit, part of the IRA, which stipulates that businesses and tax-exempt organisations that buy a qualified commercial clean vehicle may qualify under Internal Revenue Code (IRC) 45W for a clean vehicle tax credit of $7,500 for vehicles of up to 6,350kg, and $40,000 for vehicles over that weight.

Demonstrating how entrenched these tax credits were, Cox Automotive reported that the leasing rate for EVs increased from around 11% in 2022 to around 45% in 2024, which is an increase that is double the industry standard percentage. These credits being removed would disincentivise consumers even further, in turn slowing down both EV and battery demand.

The North American market does not exist in a vacuum however, and the role of foreign carmakers is not to be ignored. Some of the major players in the global EV market are Chinese firms, including BYD and Geely. Their vertical integration within the value chain has proven disruptive to the sector, as they have more agency over and resiliency in their battery supply chains compared to American counterparts. However, this disruption may not be a major factor going forward, as the previous Biden administration took steps to prohibit the sale and import of Chinese hardware and software systems. Similarly, the tariffs introduced by President Trump at the start of April further limit the flow of Chinese and other foreign battery parts into the US, which too could limit US-based EV production.

Nearshoring to strengthen battery supply

With the increased level of uncertainty, especially surrounding international cargo flows, there has been a significant rise in nearshoring as a means to reduce disruption and improve supply chain resiliency, as well as capitalise on the rising domestic market. As Kurt Kelty, vice-president of battery cell and pack at GM, puts it: “It’s a simple and pragmatic reality that development of any new technology benefits greatly from proximity to customers…[.] Today, the US has the customer base.”

Kelty’s comments represent a wider move by American OEMs to domesticate production within the EV value chain, including batteries and battery components. GM, for example, has committed to building a battery facility at its tech hub in Warren, Michigan with the goal of boosting the company’s R&D in battery tech. Similarly, last summer Ford announced plans to reshore battery production for several of its EV models, including the best-selling EV truck in the US currently, the F-150 Lightning, with the production moving from Poland to Michigan. Rivian also recently announced a $120m supplier park project attached to its EV production facility in Illinois – a move that CEO RJ Scaringe called a “key enabler” for scaling up the site’s production when the company’s R2 model launches next year.

While the price of GM’s new facility was not announced, the moves are indicative of the belief held by some American OEMs, despite any differences in scale and market share, that EVs will continue to grow and so it is worth investing the means to streamline and improve production efficiency.

Support for this idea is so strong that Kelty also stated that North America will soon become the global leader in EV battery production – an idea that has the potential to reverse the established flows of battery material and information from East to West.

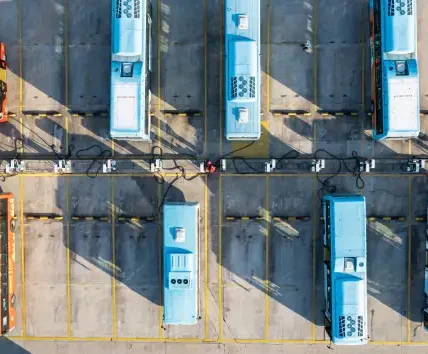

The ‘Vehicle logistics for an electric future’ panel at FVLNA dove into how US OEMs were adapting their networks to accommodate EVs

This is also seen in the steps these automakers are taking to strengthen their domestic EV and battery logistics. Shannon expanded on his earlier declaration by explaining how GM had identified problems in its EV infrastructure and taken steps to fix it. For instance, deploying mobile charging stations along both rail and road routes. Fellow panellists echoed this sentiment, talking about how – even though adjustments would be required in both mentalities and infrastructure – there was invested support in ensuring EV logistics success. However, increased communication is key to this. As Charles Franklin, Glovis America’s senior national manager for business development, succinctly put it: “We’ll ship whatever you build – I just want you to be open on what your constraints are, and then I can make it happen.”

Foreign investment

It is not only American OEMs that are taking steps to localise EV and battery production in North America. Earlier this year, Toyota revealed that its first battery manufacturing plant outside Japan, located in North Carolina, was ready to begin production. The company’s press release said that the $14 billion plant is part of its ‘best-in-town’ approach, focused on “investing and producing locally, contributing to the local community and offering products tailored to local needs through a multi-pathway strategy.”

Hyundai already has opened a metaplant in the state of Georgia following a $5.54 billion joint investment from the company and its suppliers. This is the automaker’s first dedicated EV production facility and was made with the explicit purpose of improving the stability of its US EV battery supply chain. Again, this mindset and the level of investment represents a strong vote of confidence in the continued growth of the EV market in North America from OEMs. It also reinforces how the flow of batteries might change over the coming years, as the infrastructure required for the US to become a key manufacturing hub for batteries is increasingly being created from both domestic and foreign players.

While EV and battery production sites may be domesticated, there is still the risk that the supply of battery materials further upstream may be disrupted. However, recent research from the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT) downplays this concern. Chang Shen, researcher at the ICCT, commented that “there’s more than 100 lithium mining and refining projects underway within the US and its trade partners”. With the support of these projects, the potential for North America to grow as a manufacturing hub is increased. Creating this direct flow of core battery components improves resiliency by reducing reliance on other markets and regions for a key part of EV production.

Another benefit to increased domestic mining and refining is that the distances covered in the supply of materials is significantly shorter which reduces the environmental impact of transporting them. Shorter distances between refinery and factory can therefore help American OEMs further decarbonise their supply chains and hit sustainability targets.

Scale backs and delays

Despite the optimism shared by some OEMs, others have raised concerns over the continued success of the EV market in the US and have responded by pulling away from battery-related investments. As Criss Edwards points out in his Red Sofa interview, EV sales have fallen short of expectations, which has resulted in some OEMs shifting gear. For example, while Ford plans to reshore its battery production, it is making several planned SUV model lines hybrid instead of purely electric and has said that its annual capital expenditure for EVs will drop from 40% to 30%.

Others have scaled back on planned EV expansions or delayed planned production lines. Stellantis, meanwhile, has pushed production of the electric version of the Dodge Challenger and the Ram 1500 Ramcharger back from 2026 to 2027. For the latter, this is the second pushback it’s had in as many years. Such moves bely increased caution surrounding EVs that is set to continue in the face of reduced governmental support and a projected slowdown in consumer demand.

Speaking at #FVLNA, he outlined the high level of uncertainty surrounding the domestic US EV market but was optimistic about the industry’s response.

Delays in EV production will also have an impact on the battery supply chain, easing the demand while more gigafactories come online to meet it. However, a renewed focus on hybrid models over pure EVs will maintain at least some investment in batteries from the more cautious OEMs.

So, what does the future hold for EV batteries in North America? The Global EV Outlook, published earlier in May by the International Energy Agency, forecast that sales of plug-in cars in the US will double to an overall automotive market share of 20% by 2030. While this may seem like solid growth, it is still far below the figure expected by many OEMs at the turn of the decade.

Such a difference may be alarming to some but there is still optimism from several leaders in the field, even if their approaches have adjusted. At this year’s FVL North America conference, Patrick Manzi, chief economist at the National Automobile Dealers Association, outlined several of the key problems facing the EV sector in North America, pointing to charging infrastructure and battery costs as critical roadblocks.

While the latter of these problems might be solved by nearshoring efforts, a pullback in investment might mean that the former remains a problem. In the face of all the difficulties facing the North American EV market, Manzi accurately summarised that “uncertainty is the only constant right now” but does think that “cooler heads could change that.”